About 25 miles outside of Atlanta, a large stone monolith stands alone. It’s more than 800 feet tall and about five miles in diameter. For thousands of years, Stone Mountain has been a site of human curiosity. On top, there are walls that were built up to 2,000 years ago.

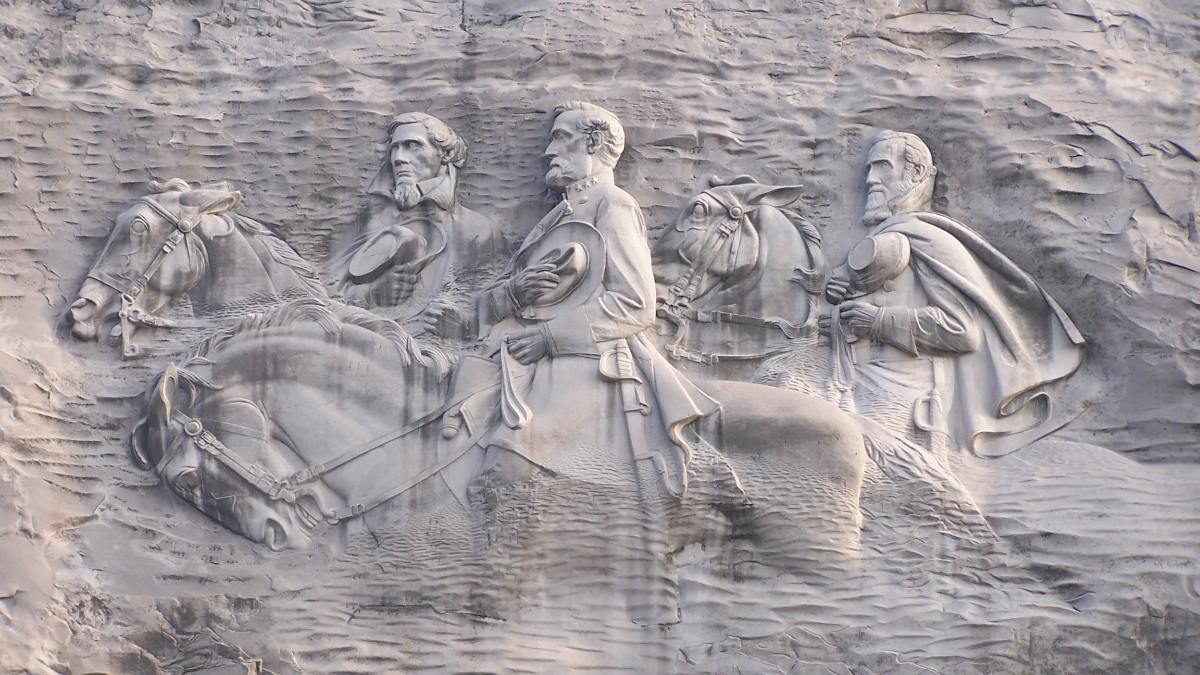

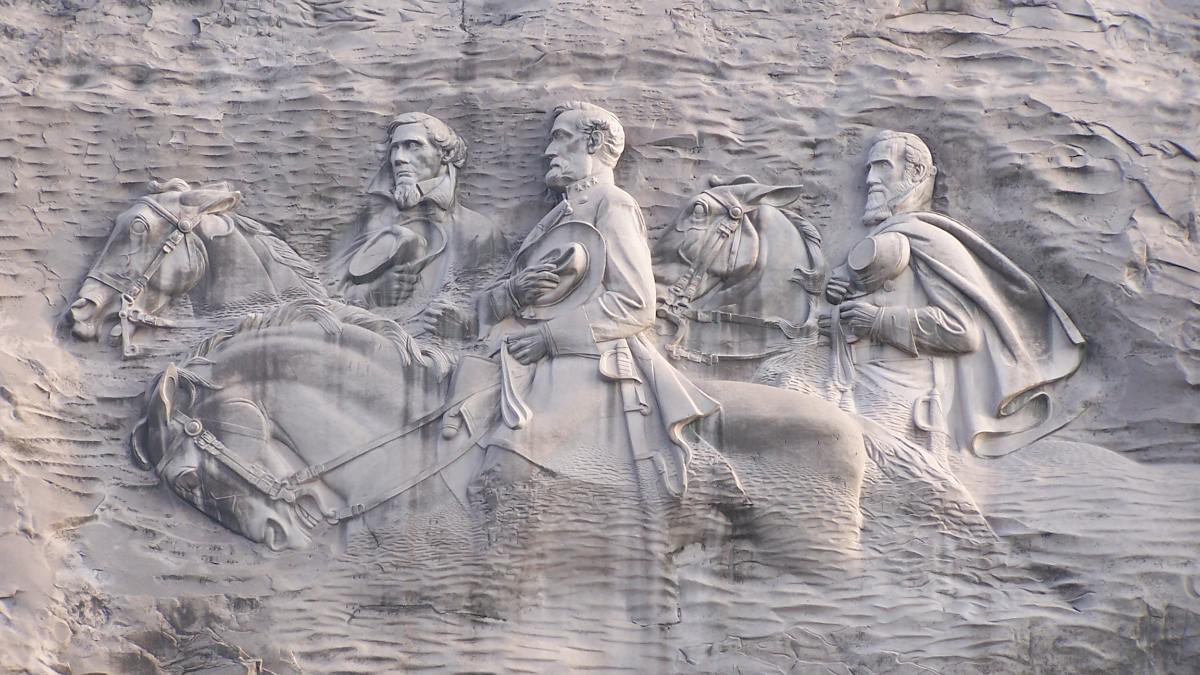

Now, when people go to visit Stone Mountain Park, they come to see a variety of things. Among them is a massive sculpture carved directly into the granite. This sculpture, which features prominent

Confederate officials, has been a trigger point for white nationalism for decades. More recently, anti-racist groups have called for the sculpture to come down. But it’s not that simple. How does one bring down a sculpture as large as a mountain?

A Century of White Supremacy Set in Stone

Georgia was one of the original seven states to secede from the U.S. as part of the Confederacy. Its participation was laden with struggle, as the state’s governor was often at odds with Confederate president Jefferson Davis. By the late 1860s, much of the state had turned to rebuilding.

It wasn’t long before people realized that they had a massive dome of granite not far from a major site of local trade. Stone Mountain became a granite quarry at this point, with people carving chunks out of it to sell to businesses in the building industry. There are granite blocks from the mountain at the U.S. Capitol, near the Panama Canal, even in Tokyo.

By 1915, people were starting to think that they ought to carve something into the rock, as well. C. Helen Plane, a confederate widow and prominent member of the

United Daughters of the Confederacy, proposed a memorial. The UDC chose Gutzon Borglum. They started to raise funds for Borglum’s sculpture plan. The land’s owner, Sam Venable, granted the deed. He also invited the local Ku Klux Klan to renew their efforts with a ceremony on top of the mountain.

But construction wasn’t as smooth as they hoped. First, Borglum was delayed by disagreements over who ought to be included in the memorial. Second, World War I distracted both funds and attention. And by the end, Borglum left to carve Mount Rushmore. So Stone Mountain sat, with only the head of General Robert E. Lee, for nearly 40 years.

The backlash to the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s brought the idea of the memorial into new relief. In the 1950s, Georgia’s governor bought the mountain with the intent of finishing the memorial. By the 1970s, it was complete. Today, it features a carving of Lee, Davis and General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. The sculpture is cut 42 feet into the mountain, starting 400 feet above the ground. The total area is about the size of a football field.

Monuments to Jim Crow

Although Stone Mountain was completed later than other monuments, the force driving it sang a similar tune. It began at the same time as the push in many areas to lionize the Confederacy. Under the “Lost Cause” ideology, people argued that confederate soldiers shouldn’t be lambasted as traitors. They believed that the principles of the Confederacy were honorable, and so they deserved to be honored.

The placement of many Confederate memorials across the country acted as part of a consolation prize. It was granted to white people unhappy about the end of slavery. This period of American history, representing the end of the Civil War up until the Civil Rights movement, is typically known as “Jim Crow.” It’s marked by a societal expectation that white people were first-class, making Black people and other people of color second-class.

American culture during this period highlighted the differences between races and argued that segregation was best. White people could no longer hold Black people in slavery. But laws established white dominance in politics, business and more. For example, some Black people could technically vote per the 15th Amendment to the Constitution in 1870. But many states set conditions on the ability to vote, which disproportionately targeted Black people. And everywhere Americans might be, particularly in the South, there were monuments idealizing white supremacy.

A Divided Society

If the idea that Black people might lose the ability to vote due to laws passed by white people sounds familiar, it should. Voting rights continue to be a hotly-contested issue that runs strongly down partisan lines. The same is generally true for Confederate memorials. In 2017, progressive groups gained momentum in the fight to bring down these monuments.

In the past few years, particularly since a group of white nationalists marched in Charlottesville, Virginia, people have fought to bring down memorials to hate. As Stacey Abrams ran for Georgia’s governor in 2017, she called attention to the Stone Mountain monument. That year ignited a push to rethink the value of such memorials, but it wasn’t until 2020 that they began to come down en masse.

If it’s a statue of a Confederate officer, it’s probably going to come down. Although it’s hard to say whether more people want to keep them or destroy them, even centrists are learning to read the room. Wikipedia keeps a page of dozens of Confederate monuments that have been removed from their places. This is just since the protests after the death of George Floyd in late May, 2020. Although some of these statues have been brought down by protesters, most have been removed by the city where they are located. A surprising number have been taken down by their owners.

What happens now is something that remains to be seen. Some statues have been hastily replaced with statues of protesters, abolitionists or other prominent Black figures. Others remain empty as interested parties fight over what to do with it.

Monuments in Flux

If this feels like a uniquely American problem, it’s not. Other regions have even more struggles to determine who gets to decide the fate of historic sites and monuments. In Iraq, Dair Mar Elia was a 6th Century Christian monastery. It was destroyed by ISIL in 2014 along with several other historic sites. Some call it an attempt to erase the Christian history of the region.

The battle of “Whose history is this?” continues in places like Turkey, as well. Very recently, Turkey’s government declared the historic site of the Hagia Sophia to be a mosque once again. Also built in the 6th Century, Hagia Sophia has been a cathedral, a mosque and a secular museum. But in the midst of this, a fight rages. Some say that the building ought to be a mosque, as it was for nearly 500 years. Others say that this change is an indicator that Turkey will marginalize non-Muslims in the country.

The Future of Stone Mountain

What can people do with a mountain? What should they do with a monument to a failed nation based on slavery? The difficulty answering these questions explains why Stone Mountain remains as it is, for now. There are a few ideas. Some suggest carving more figures into the mountain. Instead of washing over its checkered history, they could contribute to it. People have proposed carving a sculpture of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Many say it’s got to go. A few have said that sandblasting could remove the sculpture. That might act like weathering, to smooth out the carving without risking parts of the mountain falling. Others suggest a more passive route. If they simply stop maintaining it, green will grow in the gaps. Eventually, the carving will be covered and no longer visible. Only one thing seems clear. It will probably be some time before there’s a decision about Stone Mountain.

Like many things, the Confederacy lives in memory much differently than its own history. The two best-known relics of the five-year nation are racism and a series of monuments to its officials. The former may never be solved. The latter calls for a creative solution. While the answer to Confederate memorials seems to be bringing them down, Stone Mountain raises interesting questions. What does it take to bring down a mountain, and what is brought down with it?